“But

when

[Uzziah]

became

strong,

his

heart

was

so

proud

that

he

acted

corruptly,

and

he

was

unfaithful

to

the

Lord

his

God,

for

he

entered

the

temple

of

the Lord to burn incense on the altar of incense” (2 Chronicles 26:16).

“Such a Dangerous Man”

In

1859-69,

the

French

diplomat,

Ferdinand

de

Lesseps,

successfully

directed

the

effort

to

cut

a

100-mile

Suez

Canal

to

join

the

Atlantic

and

Indian

Oceans.

This

made

him

one

of

the

most

lionized

men

of

his

time.

Indeed,

so

great

was

the

confidence

in

him,

that

he

was

appointed

to

undertake

the

construction

of

the

Panama

Canal

to

connect

the

Atlantic

and

Pacific Oceans.

Yet,

the

Isthmus

of

Suez

was

relatively

flat,

making

it

possible

to

dig

a

sea-level

canal

there,

while

the

terrain

of

Panama

was

so

different

that

it

made

it

very

difficult

to

build

a

canal

without

locks

there.

De

Lesseps,

nevertheless,

was

undeterred.

Against

all

the

advice

and

warnings

of

experts,

he

adamantly

insisted

that

the

Panama

Canal

also

be

constructed

at

sea-level.

As

a

result,

the

French

effort

to

build

a

canal

across

Panama

was

a

colossal

failure

and

the

company

created

to

finance

it

went

bankrupt.

After

an

official

inquiry,

the

French

government

sentenced

de

Lesseps

to

a

five-year

imprisonment,

which

he

escaped

only

by

a

successful

appeal.

Of

de

Lesseps

and

this sad episode, historian David McCullough aptly says:

“But

the

crucial

point

is

that

[Ferdinand]

de

Lesseps

was

a

rainmaker

to

the

nineteenth

century:

he

himself

was

no

less

bedazzled

than

anyone

by

that

era’s

own

new

magical

powers.

…

It

was

he

who

had,

at

Suez,

succeeded

in

bringing

science

and

technology

to

bear

for

one

noble,

humanitarian

purpose;

and

after

that

it

had

been

very

difficult

to

doubt

his

word

or

distrust

his

vision.

From

Suez

on,

as

he

himself

once

said,

he

enjoyed

‘the

privilege

of

being

believed

without

having

to

prove

what

one

affirms.’

It

was

this

that

made

him

such

a

popular

force

and

such a dangerous man” (The Path Between the Seas, pp. 238, 239).

Benjamin

Franklin

said,

“Success

has

ruined

many

a

man.”

That

was

obviously

true

of

Ferdinand

de

Lesseps.

Success

in

Suez

ensured

his

failure

at

Panama.

This

is

understandable.

Men

are

naturally

prone

to

trust

themselves

and

all

the

more

so

when

others

affirm

their

self-worth.

Yet,

the

desire

for

the

approval

of

others

can

also

restrain

them

from

the

foolishness

to

which

their

egos

would

otherwise

drive

them.

After

all,

success,

and

the

support

for

one’s

self-image

derived

from

it,

often

depends

on

the

assistance

of

others.

In

fact,

the

success

which

so

inflated

de

Lesseps’

ego

consists

just

as

much

in

the

popular

acclaim

as

in

the

achievement

which

brings

it.

De

Lesseps

could

not

have

ruined

himself

and

others

had

he

not

had

their

assistance.

Their

unstinting

praise

and

conferral

of

infallibility

upon

him

enabled

him

to

overlook

obvious

problems

with

his

plan.

Thus,

he

could

not

have

been

as

much

a

failure

as

he

had

been

a

success

without

the

cooperation

of

thousands,

if

not

millions,

of

others.

He

became

“such

a

dangerous

man”

because

his

admirers

made

him

so.

So,

in

the

end,

it

was

not

de

Lesseps

who

was

the

greater

danger;

it

was

those

who

were

willing

to

elevate

him

to

danger.

His

big

mistake

lay

in

yielding

to

the

overwhelming

temptation

to

trust

the

masses,

who

trusted

him

to

trust

their

judgment

of

him

and

his

abilities.

To

that

extent,

they were the dangerous ones.

The

same

remains

true

today,

especially

in

the

religious

realm,

where

people

lack

the

feedback

of

physical

failure

to

hold

the

adulation

of

themselves

and

others

in

check.

All

they

have

there

is

the

Bible,

though

without

the

faith

to

trust

unquestioningly

in

it

as

God’s

infallible

word

rather

than

in

popular

judgment,

often

based

on

observation

of

circumstances,

it

does

no

good.

Anytime

anyone

allows

himself

to

be

elevated

by

the

acclaim

of

the

masses

to

practical

infallibility,

he

becomes

“such

a

dangerous

man.”

Yet,

he

can

only

be

dangerous

because

the

masses

have

made

him

so.

It

is

always

Man

who

is

the

most

dangerous man.

Copyright © 2017 - current year, Gary P. and Leslie G. Eubanks. All Rights Reserved.

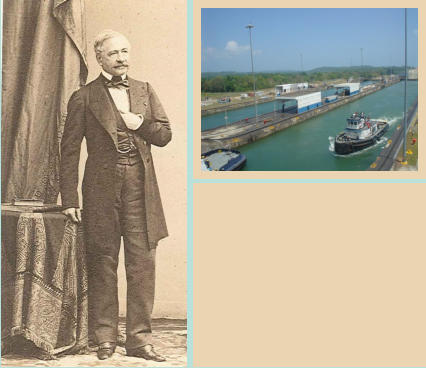

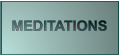

Clockwise left to right: Ferdinand de Lesseps/Panama Canal/Suez Canal

Copyright © 2017 - current year, Gary P. and Leslie G. Eubanks. All Rights Reserved.

“But

when

[Uzziah]

became

strong,

his

heart

was

so

proud

that

he

acted

corruptly,

and

he

was

unfaithful

to

the

Lord

his

God,

for

he

entered

the

temple

of

the

Lord

to

burn

incense on the altar of incense” (2 Chronicles 26:16).

“Such a Dangerous Man”

In

1859-69,

the

French

diplomat,

Ferdinand

de

Lesseps,

successfully

directed

the

effort

to

cut

a

100-mile

Suez

Canal

to

join

the

Atlantic

and

Indian

Oceans.

This

made

him

one

of

the

most

lionized

men

of

his

time.

Indeed,

so

great

was

the

confidence

in

him,

that

he

was

appointed

to

undertake

the

construction

of

the

Panama

Canal

to

connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Yet,

the

Isthmus

of

Suez

was

relatively

flat,

making

it

possible

to

dig

a

sea-level

canal

there,

while

the

terrain

of

Panama

was

so

different

that

it

made

it

very

difficult

to

build

a

canal

without

locks

there.

De

Lesseps,

nevertheless,

was

undeterred.

Against

all

the

advice

and

warnings

of

experts,

he

adamantly

insisted

that

the

Panama

Canal

also

be

constructed

at

sea-level.

As

a

result,

the

French

effort

to

build

a

canal

across

Panama

was

a

colossal

failure

and

the

company

created

to

finance

it

went

bankrupt.

After

an

official

inquiry,

the

French

government

sentenced

de

Lesseps

to

a

five-year

imprisonment,

which

he

escaped

only

by

a

successful

appeal.

Of

de

Lesseps

and

this

sad

episode,

historian

David

McCullough aptly says:

“But

the

crucial

point

is

that

[Ferdinand]

de

Lesseps

was

a

rainmaker

to

the

nineteenth

century:

he

himself

was

no

less

bedazzled

than

anyone

by

that

era’s

own

new

magical

powers.

…

It

was

he

who

had,

at

Suez,

succeeded

in

bringing

science

and

technology

to

bear

for

one

noble,

humanitarian

purpose;

and

after

that

it

had

been

very

difficult

to

doubt

his

word

or

distrust

his

vision.

From

Suez

on,

as

he

himself

once

said,

he

enjoyed

‘the

privilege

of

being

believed

without

having

to

prove

what

one

affirms.’

It

was

this

that

made

him

such

a

popular

force

and

such

a

dangerous

man”

(The

Path

Between

the

Seas,

pp. 238, 239).

Benjamin

Franklin

said,

“Success

has

ruined

many

a

man.”

That

was

obviously

true

of

Ferdinand

de

Lesseps.

Success

in

Suez

ensured

his

failure

at

Panama.

This

is

understandable.

Men

are

naturally

prone

to

trust

themselves

and

all

the

more

so

when

others

affirm

their

self-

worth.

Yet,

the

desire

for

the

approval

of

others

can

also

restrain

them

from

the

foolishness

to

which

their

egos

would

otherwise

drive

them.

After

all,

success,

and

the

support

for

one’s

self-image

derived

from

it,

often

depends

on

the

assistance

of

others.

In

fact,

the

success

which

so

inflated

de

Lesseps’

ego

consists

just

as

much

in

the

popular

acclaim

as

in

the

achievement

which

brings

it.

De

Lesseps

could

not

have

ruined

himself

and

others

had

he

not

had

their

assistance.

Their

unstinting

praise

and

conferral

of

infallibility

upon

him

enabled

him

to

overlook

obvious

problems

with

his

plan.

Thus,

he

could

not

have

been

as

much

a

failure

as

he

had

been

a

success

without

the

cooperation

of

thousands,

if

not

millions,

of

others.

He

became

“such

a

dangerous

man”

because

his

admirers

made

him

so.

So,

in

the

end,

it

was

not

de

Lesseps

who

was

the

greater

danger;

it

was

those

who

were

willing

to

elevate

him

to

danger.

His

big

mistake

lay

in

yielding

to

the

overwhelming

temptation

to

trust

the

masses,

who

trusted

him

to

trust

their

judgment

of

him

and

his

abilities.

To

that

extent,

they

were

the

dangerous ones.

The

same

remains

true

today,

especially

in

the

religious

realm,

where

people

lack

the

feedback

of

physical

failure

to

hold

the

adulation

of

themselves

and

others

in

check.

All

they

have

there

is

the

Bible,

though

without

the

faith

to

trust

unquestioningly

in

it

as

God’s

infallible

word

rather

than

in

popular

judgment,

often

based

on

observation

of

circumstances,

it

does

no

good.

Anytime

anyone

allows

himself

to

be

elevated

by

the

acclaim

of

the

masses

to

practical

infallibility,

he

becomes

“such

a

dangerous

man.”

Yet,

he

can

only

be

dangerous

because

the

masses

have

made

him

so.

It

is

always Man who is the most dangerous man.

Clockwise left to right: Ferdinand de Lesseps/Panama Canal/Suez Canal