“Do

not

say,

‘Why

is

it

that

the

former

days

were

better

than

these?’

For

it

is not from wisdom that you ask about this” (Ecclesiastes 7:10).

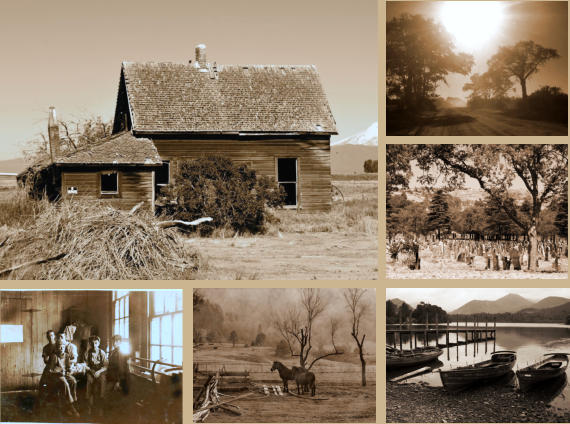

Nostalgia

It

is

a

trait

of

human

nature,

not

just

to

be

able

to

remember

the

past,

but

seemingly

to

relish

and

love

doing

so.

People

cherish

sentimental

objects

from

long

ago,

they

preserve

love

letters

and

other

such

tokens

of

their

personal

history,

they

pore

over

the

mementos

of

their

youth,

they

visit

and

adorn

the

graves

of

their

loved

ones,

they

reminisce

over

old

photographs,

and

in

innumerable

other

ways

yearn

for

yore,

as

if

seeking

to

restore

and

relive

it,

pausing

to

muse

on

these

reminders

of

what

once

was

—

and, perhaps, over what was to be but never was.

While

some

are

more

wistful

than

others,

everyone

indulges

nostalgia.

This

is

strange,

if

not

surprising,

considering

that

it

is

bittersweet.

In

fact,

“nostalgia”

comes

from

two

Greek

words

(nostos,

“homecoming,”

and

algos,

“pain”)

which

were

combined

“around

the

time

of

the

American

Revolution

as

a

medical

term

for

melancholia

caused

by

homesickness”

(

Family

Word

Finder

,

pg.

540).

Perhaps

this

is

nowhere

more

evident

than

in

reunions

of

military

veterans

who

gather

to

remember

wartime

experiences.

They

do

this

though

much

of

what

they

recall

hurts.

Looking

at

photographs

of

deceased

loved

ones

might

be

pleasant,

but

the

memories

they

evoke

still

bear

an

underlying

ache

from the consciousness that they are gone beyond reach.

It

is

hard

to

say

that

something

so

natural,

so

much

an

instinctual,

even

unique,

part

of

the

human

psyche

could

be

wrong

or

bad.

Indeed,

it

can

be

very

detrimental

not

to

remember

the

past.

All

learning

requires

it.

Even

the

moral

component

in

remembering

the

past

is

evoked

by

the

aphorism

of

the

philosopher,

George

Santayana,

who said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

It

is

not

difficult

to

discern

the

drive

behind

nostalgia.

It

is

a

reversion

to

the

past.

None

can

relive

it,

but

one

can

approach

it

by

vividly

remembering

it,

aided

by

its

physical

remnants.

Thus,

when

a

man

lingers

and

muses

over

a

childhood

photograph

of

himself,

for

a

brief

moment,

he

is

able

to

return

in

his

mind

to

a

time

when

the

future,

not

yet

made,

can

again

be

contemplated

with

promise,

hope,

and

optimism

—

when

the

mistakes

to

be

made

are,

not

only

not

yet

made,

but

do

not

have

to

be

made

—

to

a

time

when

things

could

be

so

much

better

than

they

might

have

turned

out

to

be.

He

can

go

back

to

a

place

where

life

was

young

and

fresh

and

vistas

of

opportunity

opened

before

him.

Perhaps

no

one

captures

this

better

than

William

Faulkner

in

his

Intruder

in

the

Dust

,

when

he

describes

how

the

moment

just

before

Confederate

general

George

Pickett’s

disastrous

charge

at

Gettysburg

is

conceived:

“For

every

Southern

boy

fourteen

years

old,

not

once

but

whenever

he

wants

it,

there

is

the

instant

when

it’s

still

not

yet

two

o’clock

on

that

July

afternoon

in

1863

…

.

It’s

all

in

the

balance,

it

hasn’t

happened

yet,

it

hasn’t

even

begun

yet,

it

not

only

hasn’t

begun

yet

but

there

is

still

time

for

it

not

to

begin

…

.”

These

words

apply

to

every

sad

or

tragic

event

in

life.

The

artifacts

of

the

past

can

transport

one

back

to

a

time

when

the

mind

can

entertain

the

fantasy

that

what

happened need not happen.

Time

cannot

be

recaptured

nor

history

retrieved

and

changed.

Yet,

mistakes

do

not

have

to

be

repeated.

Indeed,

going

forward,

they

can

be

cancelled

out.

The

past

can

be

made

a

springboard

to

a

future

better

than

the

past

itself.

Paul’s

assertion

that

he

forgot

what

lay

behind

(Phil.

3:13,14)

seems

strange

in

view

of

the

fact

that

he

so

often

recalled it (cf. vss. 5,6). Yet, he forgot it in that he did not allow it to control his

future.

Nostalgia

must

be

something

more

than

an

empty,

self-indulgent,

stultifying

wallowing

in

melancholia.

Instead,

the

past

must

be

allowed

to

teach

and

reach

toward a better future.

Copyright © 2017 - current year, Gary P. and Leslie G. Eubanks. All Rights Reserved.

“Do

not

say,

‘Why

is

it

that

the

former

days

were

better

than

these?’

For

it

is

not

from

wisdom

that

you

ask

about

this”

(Ecclesiastes 7:10).

Nostalgia

It

is

a

trait

of

human

nature,

not

just

to

be

able

to

remember

the

past,

but

seemingly

to

relish

and

love

doing

so.

People

cherish

sentimental

objects

from

long

ago,

they

preserve

love

letters

and

other

such

tokens

of

their

personal

history,

they

pore

over

the

mementos

of

their

youth,

they

visit

and

adorn

the

graves

of

their

loved

ones,

they

reminisce

over

old

photographs,

and

in

innumerable

other

ways

yearn

for

yore,

as

if

seeking

to

restore

and

relive

it,

pausing

to

muse

on

these

reminders

of

what

once was — and, perhaps, over what was to be but never was.

While

some

are

more

wistful

than

others,

everyone

indulges

nostalgia.

This

is

strange,

if

not

surprising,

considering

that

it

is

bittersweet.

In

fact,

“nostalgia”

comes

from

two

Greek

words

(nostos,

“homecoming,”

and

algos,

“pain”)

which

were

combined

“around

the

time

of

the

American

Revolution

as

a

medical

term

for

melancholia

caused

by

homesickness”

(

Family

Word

Finder

,

pg.

540).

Perhaps

this

is

nowhere

more

evident

than

in

reunions

of

military

veterans

who

gather

to

remember

wartime

experiences.

They

do

this

though

much

of

what

they

recall

hurts.

Looking

at

photographs

of

deceased

loved

ones

might

be

pleasant,

but

the

memories

they

evoke

still

bear

an

underlying

ache from the consciousness that they are gone beyond reach.

It

is

hard

to

say

that

something

so

natural,

so

much

an

instinctual,

even

unique,

part

of

the

human

psyche

could

be

wrong

or

bad.

Indeed,

it

can

be

very

detrimental

not

to

remember

the

past.

All

learning

requires

it.

Even

the

moral

component

in

remembering

the

past

is

evoked

by

the

aphorism

of

the

philosopher,

George

Santayana,

who

said,

“Those

who

cannot

remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

It

is

not

difficult

to

discern

the

drive

behind

nostalgia.

It

is

a

reversion

to

the

past.

None

can

relive

it,

but

one

can

approach

it

by

vividly

remembering

it,

aided

by

its

physical

remnants.

Thus,

when

a

man

lingers

and

muses

over

a

childhood

photograph

of

himself,

for

a

brief

moment,

he

is

able

to

return

in

his

mind

to

a

time

when

the

future,

not

yet

made,

can

again

be

contemplated

with

promise,

hope,

and

optimism

—

when

the

mistakes

to

be

made

are,

not

only

not

yet

made,

but

do

not

have

to

be

made

—

to

a

time

when

things

could

be

so

much

better

than

they

might

have

turned

out

to

be.

He

can

go

back

to

a

place

where

life

was

young

and

fresh

and

vistas

of

opportunity

opened

before

him.

Perhaps

no

one

captures

this

better

than

William

Faulkner

in

his

Intruder

in

the

Dust

,

when

he

describes

how

the

moment

just

before

Confederate

general

George

Pickett’s

disastrous

charge

at

Gettysburg

is

conceived:

“For

every

Southern

boy

fourteen

years

old,

not

once

but

whenever

he

wants

it,

there

is

the

instant

when

it’s

still

not

yet

two

o’clock

on

that

July

afternoon

in

1863

…

.

It’s

all

in

the

balance,

it

hasn’t

happened

yet,

it

hasn’t

even

begun

yet,

it

not

only

hasn’t

begun

yet

but

there

is

still

time

for

it

not

to

begin

…

.”

These

words

apply

to

every

sad

or

tragic

event

in

life.

The

artifacts

of

the

past

can

transport

one

back

to

a

time

when

the

mind

can

entertain the fantasy that what happened need not happen.

Time

cannot

be

recaptured

nor

history

retrieved

and

changed.

Yet,

mistakes

do

not

have

to

be

repeated.

Indeed,

going

forward,

they

can

be

cancelled

out.

The

past

can

be

made

a

springboard

to

a

future

better

than

the

past

itself.

Paul’s

assertion

that

he

forgot

what

lay

behind

(Phil.

3:13,14)

seems

strange

in

view

of

the

fact

that

he

so

often

recalled

it

(cf.

vss.

5,6).

Yet,

he

forgot

it

in that he did not allow it to control his future.

Nostalgia

must

be

something

more

than

an

empty,

self-

indulgent,

stultifying

wallowing

in

melancholia.

Instead,

the

past

must be allowed to teach and reach toward a better future.