“And

the

Pharisees

and

Sadducees

came

up,

and

testing

Him

asked

Him

to

show

them

a

sign

from

heaven.

But

He

answered

and

said

to

them,

‘When

it

is

evening,

you

say,

“It

will

be

fair

weather,

for

the

sky

is

red.”

And

in

the

morning,

“There

will

be

a

storm

today,

for

the

sky

is

red

and

threatening.”

Do

you

know

how

to

discern

the

appearance

of

the

sky,

but

cannot

discern

the

signs

of

the

times?

An

evil

and

adulterous

generation

seeks

after

a

sign;

and

a

sign

will not be given it, except the sign of Jonah.’ And He left them, and went away”

(Matt. 16:1-4).

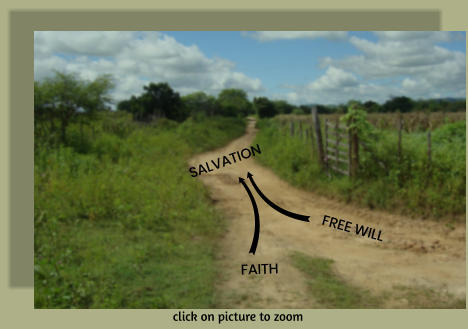

Faith and Free Will

One

of

the

most

challenging

questions

about

faith

is

why

God

has

not

done

more

to make Himself known and put His existence beyond the possibility of doubt.

It

is

not

that

hard

to

imagine

what

God

could

have

done,

but

did

not

do,

to

cause

faith.

He

could

show

Himself

directly.

He

could

also

stand

people

on

the

precipice

of

hell

or

show

them

the

splendor

of

heaven.

He

could

eliminate

suffering.

An

omnipotent

God

is

capable

of

doing

a

thousand

things

to

eliminate

unbelief.

Yet,

it

not only persists, it prevails.

This

idea

that

people

will

believe

if

God

will

just

meet

their

conditions

for

faith

also

presents

itself

in

the

Bible

several

times

in

one

form

or

another.

When

the

Pharisees

asked

of

Jesus

a

sign

from

heaven,

He

refused

their

demand

(Matt.

16:1-4).

The

(formerly)

rich

man

in

Hades

assured

Abraham

that,

if

he

would

just

send

a

risen

Lazarus

back

to

his

five

living

brothers,

they

would

believe

and

repent

(Lk.

16:27-31),

but

his

request

was

also

denied.

The

Jewish

leaders

assured

Christ

that

they

would

believe

in

Him

if

He

would

but

come

down

from

the

cross

(Matt.

27:41,42),

but

He

remained there and died.

So,

why

does

the

God

who

wishes

for

all

to

repent

and

be

saved

(1

Tim.

2:4;

2

Pet.

3:9) not do all He could do to effect the salvation of every individual?

Anyone

who

would

have

had

the

kinds

of

experiences

in

the

previous

examples,

could

do

nothing

other

than

acknowledge

God.

Yet,

that

is

exactly

what

would

make

these

experiences

inadequate

as

solutions

to

the

problem

of

unbelief.

Any

approach

which

would

correct

unbelief

by

leaving

people

no

choice

but

to

recognize

God,

by

definition

deprives

them

of

free

will.

Faith

must

be

a

choice,

not

a

compulsion

—

even

an

intellectual

compulsion.

If

it

is

not

free,

it

is

not

faith.

Paul

expresses

this

idea,

though

he

applies

it

to

hope,

when

He

says,

“…

Hope

that

is

seen

is

not

hope;

for

why

does one also hope for what he sees?” (Rom. 8:24).

The

Bible

distinguishes

between

what

a

person

knows

by

seeing

and

what

he

believes

by

inferring

a

conclusion

from

evidence

consisting

of

something

less

than

direct

experience

of

the

unseen

God.

Paul

said,

“For

we

walk

by

faith,

not

by

sight”

(2

Cor.

5:7).

Also,

the

writer

of

Hebrews

said

that

faith

consists

in

“the

conviction

of

things

not seen” (11:1).

To

appreciate

this

distinctive

and

necessary

feature

of

faith,

it

might

be

asked,

“Why

does

God

wish

for

one’s

faith

to

be

something

he

freely

chooses?”

It

is

because

it

is

the

fact

that

faith

is

a

choice

that

it

is

valuable.

Recipients

of

gifts

freely

given

from love readily understand this.

So,

the

evidence

God

provides

is

enough

both

to

produce

faith

and

to

preserve

free

will

,

and

the

only

way

that

God

can

arrange

for

faith

and

free

will

to

co-exist

in

the

same

mind

at

the

same

time

is

to

give

a

person

as

much

evidence

as

he

needs

but

not as much as he might

desire

. That way,

he

gets to decide whether he will believe.

God

wants

people

who

are

with

Him

in

heaven,

not

because

they

had

no

choice,

but

because,

though

they

could

have

done

otherwise,

they

freely

chose

to

believe

in

Him

and

love

Him.

When

Christ’s

bride,

the

church,

joins

Him

in

heaven,

it

will

not

be

by

virtue

of

a

celestial

“shotgun

wedding.”

“And

the

Spirit

and

the

bride

say,

Come

.…

And

whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely” (Rev. 22:17, KJV).

Copyright © 2017 - current year, Gary P. and Leslie G. Eubanks. All Rights Reserved.

“And

the

Pharisees

and

Sadducees

came

up,

and

testing

Him

asked

Him

to

show

them

a

sign

from

heaven.

But

He

answered

and

said

to

them,

‘When

it

is

evening,

you

say,

“It

will

be

fair

weather,

for

the

sky

is

red.”

And

in

the

morning,

“There

will

be

a

storm

today,

for

the

sky

is

red

and

threatening.”

Do

you

know

how

to

discern

the

appearance

of

the

sky,

but

cannot

discern

the

signs

of

the

times?

An

evil

and

adulterous

generation

seeks

after

a

sign;

and

a

sign

will

not

be

given

it,

except

the

sign

of

Jonah.’

And

He

left

them,

and

went

away”

(Matt. 16:1-4).

Faith and Free Will

One

of

the

most

challenging

questions

about

faith

is

why

God

has

not

done

more

to

make

Himself

known

and

put

His existence beyond the possibility of doubt.

It

is

not

that

hard

to

imagine

what

God

could

have

done,

but

did

not

do,

to

cause

faith.

He

could

show

Himself

directly.

He

could

also

stand

people

on

the

precipice

of

hell

or

show

them

the

splendor

of

heaven.

He

could

eliminate

suffering.

An

omnipotent

God

is

capable

of

doing

a

thousand

things

to

eliminate unbelief. Yet, it not only persists, it prevails.

This

idea

that

people

will

believe

if

God

will

just

meet

their

conditions

for

faith

also

presents

itself

in

the

Bible

several

times

in

one

form

or

another.

When

the

Pharisees

asked

of

Jesus

a

sign

from

heaven,

He

refused

their

demand

(Matt.

16:1-

4).

The

(formerly)

rich

man

in

Hades

assured

Abraham

that,

if

he

would

just

send

a

risen

Lazarus

back

to

his

five

living

brothers,

they

would

believe

and

repent

(Lk.

16:27-31),

but

his

request

was

also

denied.

The

Jewish

leaders

assured

Christ

that

they

would

believe

in

Him

if

He

would

but

come

down

from

the

cross

(Matt.

27:41,42),

but

He

remained

there

and

died.

So,

why

does

the

God

who

wishes

for

all

to

repent

and

be

saved

(1

Tim.

2:4;

2

Pet.

3:9)

not

do

all

He

could

do

to

effect

the salvation of every individual?

Anyone

who

would

have

had

the

kinds

of

experiences

in

the

previous

examples,

could

do

nothing

other

than

acknowledge

God.

Yet,

that

is

exactly

what

would

make

these

experiences

inadequate

as

solutions

to

the

problem

of

unbelief.

Any

approach

which

would

correct

unbelief

by

leaving

people

no

choice

but

to

recognize

God,

by

definition

deprives

them

of

free

will.

Faith

must

be

a

choice,

not

a

compulsion

—

even

an

intellectual

compulsion.

If

it

is

not

free,

it

is

not

faith.

Paul

expresses

this

idea,

though

he

applies

it

to

hope,

when

He

says,

“…

Hope

that

is

seen

is

not

hope;

for

why

does one also hope for what he sees?” (Rom. 8:24).

The

Bible

distinguishes

between

what

a

person

knows

by

seeing

and

what

he

believes

by

inferring

a

conclusion

from

evidence

consisting

of

something

less

than

direct

experience

of

the

unseen

God.

Paul

said,

“For

we

walk

by

faith,

not

by

sight”

(2

Cor.

5:7).

Also,

the

writer

of

Hebrews

said

that

faith

consists in “the conviction of things not seen” (11:1).

To

appreciate

this

distinctive

and

necessary

feature

of

faith,

it

might

be

asked,

“Why

does

God

wish

for

one’s

faith

to

be

something

he

freely

chooses?”

It

is

because

it

is

the

fact

that

faith

is

a

choice

that

it

is

valuable.

Recipients

of

gifts

freely given from love readily understand this.

So,

the

evidence

God

provides

is

enough

both

to

produce

faith

and

to

preserve

free

will

,

and

the

only

way

that

God

can

arrange

for

faith

and

free

will

to

co-exist

in

the

same

mind

at

the

same

time

is

to

give

a

person

as

much

evidence

as

he

needs

but

not

as

much

as

he

might

desire

.

That

way,

he

gets to decide whether he will believe.

God

wants

people

who

are

with

Him

in

heaven,

not

because

they

had

no

choice,

but

because,

though

they

could

have

done

otherwise,

they

freely

chose

to

believe

in

Him

and

love

Him.

When

Christ’s

bride,

the

church,

joins

Him

in

heaven,

it

will

not

be

by

virtue

of

a

celestial

“shotgun

wedding.”

“And

the

Spirit

and

the

bride

say,

Come.

…

And

whosoever

will,

let

him take the water of life freely” (Rev. 22:17, KJV).