“Peter,

turning

around,

saw

the

disciple

whom

Jesus

loved

following

them

….

Peter

therefore

seeing

him

said

to

Jesus,

‘Lord,

and

what

about

this

man?’

Jesus

said

to

him,

‘If

I

want

him

to

remain

until

I

come,

what

is

that

to

you?

You

follow

Me!’

This

saying

therefore

went

out

among

the

brethren

that

that

disciple

would

not

die;

yet

Jesus

did

not

say

to

him

that

he

would

not die, but only, ‘If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you?’”

(John 21:20-23)

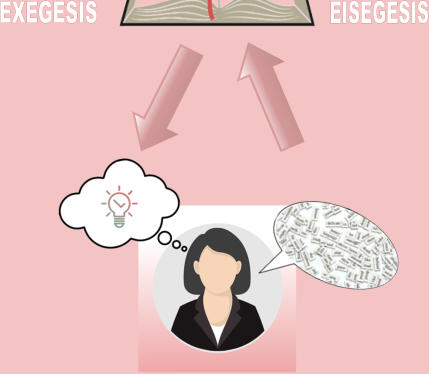

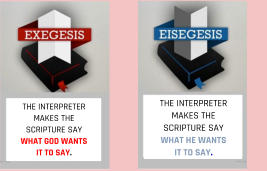

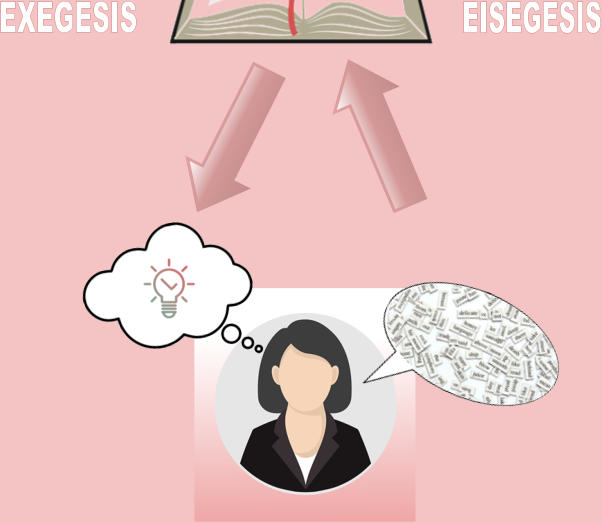

Exegesis and Eisegesis

This

text

well

illustrates

the

difference

between

two

words

which

vary

but

little

in

form,

though

widely

in

meaning.

Both

“

ex

egesis”

and

“

eis

egesis”

are

derived

from

the

same

Greek

root,

ago

,

meaning

“to

lead,

draw,

or

bring.”

Yet,

the

prepositional

prefixes,

ex

and

eis

,

which

mean

“out

of”

and

“into,”

respectively,

are

enough

to

create

words

with

quite

opposite

meanings.

Thus,

“

ex

egesis”

means

to

“lead,

draw,

or

bring

out

”

the

ideas

of

a

text,

or

“to

explain

or

interpret

its

meaning.”

“

Eis

egesis,”

on

the

other

hand,

means

to

“lead,

draw,

or

bring

[a

meaning]

into

”

a

text.

So,

it

all

comes

down

to

whether

the

Bible

reader

“leads

into”

the

text

his

own

ideas

or

“leads

out

of”

it

the

ideas

of

the

author,

who,

in

this

case,

is

God.

Of

course,

the

temptation

to

do

the

latter

results from the reader’s wish to give his ideas the ring of divine legitimacy.

Thus,

a

few

letters’

difference

in

two

little

prepositions

quite

literally

spells

a

huge

and

infinitely

critical

difference

in

meaning.

It

is

the

difference

between

what

the

Bible

actually

means

and

what

the

reader

wants

it

to

mean

.

If

it

is

asked

why

people

can

read

the

same

Bible

and,

yet,

come

to

so

many

differing

conclusions

as

to

what

it

means,

it

is

really

no

harder

to

understand

than

the

difference

between

these

two

words.

Understanding

the

Bible

depends

on

whether

the

reader

truly wishes to “bring

out

” its ideas. Otherwise, he will simply “bring

into

” it his own ideas.

The

first

generation

of

Christians

appears

to

have

wanted

and

expected

Christ

to

return

within

their

lifetimes

(cf.

2

Pet.

3:3,4).

If

so,

perhaps

this

explains

why

they

“read

into”

Christ’s

words

to

Peter

about

the

“disciple

whom

He

loved”

a

meaning

which

He

neither

intended

nor

His

words

rightly

bear.

Thus,

all

that

was

necessary

for

John

to

correct

this

misinterpretation

of

His

words

was

simply

to

repeat

them.

This

shows

that

nothing

more

is

needed

to

understand

what

Jesus

meant

than

a

careful

and

honest

reading

of

His

words.

This

is

(proper)

exegesis.

Yet,

some,

as

here,

want

to

“read

into”

(eisegesis)

the

Bible’s

words

what

is

not

really

there,

and,

thus,

they

misunderstand

it,

because

they

are

“leading

into”

it

from

their

minds

what

they

want

it

to

say

instead of simply “leading out of” it what is already there and putting that into their minds.

The

story

is

told

of

a

religious

debate

on

the

question

of

whether

“baptism”

involves

sprinkling

with

water

or

immersion

in

it.

The

debater

in

favor

of

the

idea

that

baptism

is

sprinkling

argued

his

proposition

on

the

basis

of

possible,

though

irregular,

meanings

of

key

terms.

His

opponent

responded

by

observing

that,

by

his

opponent’s

methods

and

logic,

possible

dictionary

meanings

of

the

words,

“believe,”

“baptized,”

and

“saved”

as

“to

have

an

opinion,”

“to

be

sprinkled,”

and

“to

be

pickled,”

respectively,

would

result

in

“he

who

has

believed

and

has

been

baptized

shall

be

saved”

(Mk.

16:16)

meaning

“he

who

has

an

opinion

and

has

been

sprinkled

shall

be

pickled”!

Then,

he

closed

with

the

question,

“Is

it

our

purpose

to

see

what

we

can

make

the

Bible

mean,

or

is

it our purpose to see what it

does

mean?”

When

a

reader

explains

the

Bible

to

mean

what

he

wishes

it

to

mean

instead

of

what

it

actually

means,

he

is

guilty

of

dishonesty.

He

is

telling

the

ultimate

lie

by

committing

the

blasphemy of displacing God’s ideas with his own and calling them God’s.

“Peter,

turning

around,

saw

the

disciple

whom

Jesus

loved

following

them

….

Peter

therefore

seeing

him

said

to

Jesus,

‘Lord,

and

what

about

this

man?’

Jesus

said

to

him,

‘If

I

want

him

to

remain

until

I

come,

what

is

that

to

you?

You

follow

Me!’

This

saying

therefore

went

out

among

the

brethren

that

that

disciple

would

not

die;

yet

Jesus

did

not

say

to

him

that

he

would

not

die,

but

only,

‘If

I

want

him

to

remain

until I come, what is that to you?’”

(John 21:20-23)

Exegesis and Eisegesis

This

text

well

illustrates

the

difference

between

two

words

which

vary

but

little

in

form,

though

widely

in

meaning.

Both

“

ex

egesis”

and

“

eis

egesis”

are

derived

from

the

same

Greek

root,

ago

,

meaning

“to

lead,

draw,

or

bring.”

Yet,

the

prepositional

prefixes,

ex

and

eis

,

which

mean

“out

of”

and

“into,”

respectively,

are

enough

to

create

words

with

quite

opposite

meanings.

Thus,

“

ex

egesis”

means

to

“lead,

draw,

or

bring

out

”

the

ideas

of

a

text,

or

“to

explain

or

interpret

its

meaning.”

“

Eis

egesis,”

on

the

other

hand,

means

to

“lead,

draw,

or

bring

[a

meaning]

into

”

a

text.

So,

it

all

comes

down

to

whether

the

Bible

reader

“leads

into”

the

text

his

own

ideas

or

“leads

out

of”

it

the

ideas

of

the

author,

who,

in

this

case,

is

God.

Of

course,

the

temptation

to

do

the

latter

results

from

the reader’s wish to give his ideas the ring of divine legitimacy.

Thus,

a

few

letters’

difference

in

two

little

prepositions

quite

literally

spells

a

huge

and

infinitely

critical

difference

in

meaning.

It

is

the

difference

between

what

the

Bible

actually

means

and

what

the

reader

wants

it

to

mean

.

If

it

is

asked

why

people

can

read

the

same

Bible

and,

yet,

come

to

so

many

differing

conclusions

as

to

what

it

means,

it

is

really

no

harder

to

understand

than

the

difference

between

these

two

words.

Understanding

the

Bible

depends

on

whether

the

reader

truly

wishes

to

“bring

out

”

its

ideas.

Otherwise, he will simply “bring

into

” it his own ideas.

The

first

generation

of

Christians

appears

to

have

wanted

and

expected

Christ

to

return

within

their

lifetimes

(cf.

2

Pet.

3:3,4).

If

so,

perhaps

this

explains

why

they

“read

into”

Christ’s

words

to

Peter

about

the

“disciple

whom

He

loved”

a

meaning

which

He

neither

intended

nor

His

words

rightly

bear.

Thus,

all

that

was

necessary

for

John

to

correct

this

misinterpretation

of

His

words

was

simply

to

repeat

them.

This

shows

that

nothing

more

is

needed

to

understand

what

Jesus

meant

than

a

careful

and

honest

reading

of

His

words.

This

is

(proper)

exegesis.

Yet,

some,

as

here,

want

to

“read

into”

(eisegesis)

the

Bible’s

words

what

is

not

really

there,

and,

thus,

they

misunderstand

it,

because

they

are

“leading

into”

it

from

their

minds

what

they

want

it

to

say

instead

of

simply

“leading

out

of” it what is already there and putting that into their minds.

The

story

is

told

of

a

religious

debate

on

the

question

of

whether

“baptism”

involves

sprinkling

with

water

or

immersion

in

it.

The

debater

in

favor

of

the

idea

that

baptism

is

sprinkling

argued

his

proposition

on

the

basis

of

possible,

though

irregular,

meanings

of

key

terms.

His

opponent

responded

by

observing

that,

by

his

opponent’s

methods

and

logic,

possible

dictionary

meanings

of

the

words,

“believe,”

“baptized,”

and

“saved”

as

“to

have

an

opinion,”

“to

be

sprinkled,”

and

“to

be

pickled,”

respectively,

would

result

in

“he

who

has

believed

and

has

been

baptized

shall

be

saved”

(Mk.

16:16)

meaning

“he

who

has

an

opinion

and

has

been

sprinkled

shall

be

pickled”!

Then,

he

closed

with

the

question,

“Is

it

our

purpose

to

see

what

we

can

make

the

Bible

mean,

or

is

it

our

purpose to see what it

does

mean?”

When

a

reader

explains

the

Bible

to

mean

what

he

wishes

it

to

mean

instead

of

what

it

actually

means,

he

is

guilty

of

dishonesty.

He

is

telling

the

ultimate

lie

by

committing

the

blasphemy

of

displacing God’s ideas with his own and calling them God’s.