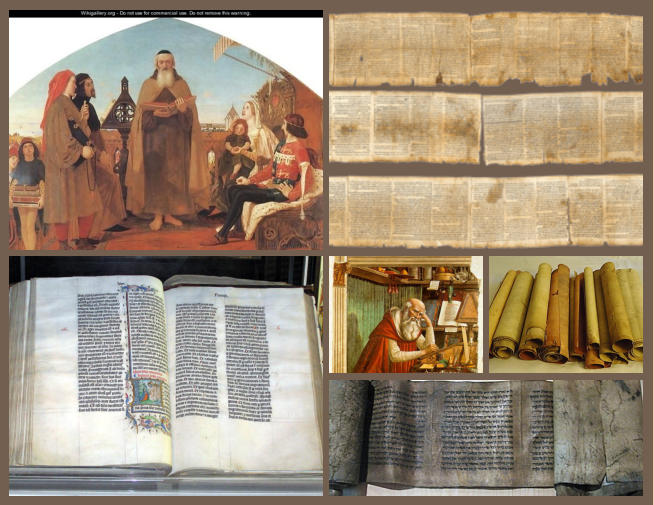

top,

left

to

right

-

"The

First

Translation

of

the

Bible

into

English:

Wycliffe

Reading

His

Translation

of

the

Bible

to

John

of

Gaunt";

“The Great Isaiah Scroll” - housed in the Shrine of the Book in the Israel Museum

middle,

left

to

right

-

“

Saint

Jerome

in

His

Study,”

fresco

by

Domenico

Ghirlandaio

located

in

the

church

of

Ognissanti,

Florence;

100-600-year-old scrolls from a private collection

bottom, left to right - A Bible handwritten in Latin, on display in Malmesbury Abbey, Wiltshire, England; “The Book of Esther,” from

the 13th or 14th Century, on display at the Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France

---all attributions at page bottom---

• Ford Madox Brown – Creative Commons license, via Wikipedia Commons

• Ardon Bar Hama, author of original document is unknown, Public domain, via Wikipedia Commons

• Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License 3.0, via Wikipedia Commons

• Mike Izbicki, 2014-08-10- scribal traditions of "ancient" Hebrew scrolls, Creative Commons attribution-share alike

• Adrian Pingstone. Public domain, via Wikipedia Commons

• Deror avi, 2009-02-13, Public domain, via Wikipedia Commons

“And

I

saw

the

dead,

the

great

and

the

small,

standing

before

the

throne,

and

books

were

opened;

and

another

book

was

opened,

which

is

the

book

of

life;

and

the

dead

were

judged

from the things which were written in the books, according to their deeds” (Revelation 20:12).

Codex: the Bible Becomes the Bible

The

use

of

“book”

in

the

Bible

is

an

anachronism,

since

books,

as

they

are

known

today,

did

not

then

exist.

Instead,

ancient

“books”

were

“scrolls,”

or

rolls

of

papyrus,

which

were

opened

by

being

unwound.

When

Jesus

“closed

the

book”

of

Isaiah

in

the

Nazareth

synagogue,

He

“rolled”

it

up

(Lk.

4:20).

John

said

the

sky

was

“split

apart

like

a

scroll

when

it

is

rolled

up”

(Rev.

6:14),

and

the

Psalmist

refers

to

“the

roll

of

the

book”

(cf.

Psa.

40:7;

Heb.

10:7,

NASB).

Thus,

to

translate

the

Greek

words,

“biblion”

or

“biblos”

(whence,

“Bible”),

as

“book”

is

an

accommodation

to

modern

conceptions.

Moving

to

different

parts

of

a

scroll

was

cumbersome.

Bible

readers

are

now

accustomed

to

being

able

to

move

quickly

from

one

text

to

another,

but

this

was

not

easily

done

by

scroll

users.

In

fact,

the

larger

books

of

the

Bible

by

themselves

might

occupy

all

the

space

of

a

single

scroll.

For

example,

when

Jesus

was

given

the

scroll

of

Isaiah

(Lk.

4:17),

He

presumably

had

to

unroll

it

almost to its end to find the place from which He read (Isa. 61:1ff).

Adding

the

twenty-seven

New

Testament

books

increased

the

size

of

the

Bible

and

the

occasion

to

move

rapidly

among

Biblical

texts

for

cross-referencing.

So,

having

sixty-six

books

on

scrolls became inconvenient, if not untenable, for the kind of Bible study which was needed.

This

situation

led

to

the

development

of

the

codex,

which

was

essentially

the

modern

book.

Codices

allowed

texts

to

be

written

on

the

fronts

and

backs

of

leaves,

or

pages,

which

were

piled

atop

one

another

in

textual

order

and

bound

together

by

stitching

on

one

edge

to

produce

a

book.

The

codex

had

the

great

advantage

of

giving

readers

access

to

a

large

amount

of

text

in

a

much

more

compact

and

usable

form,

and

especially

of

allowing

them

to

move

easily

from

one

text

to

another.

In

fact,

Christians

are

credited

with

having

developed,

or

popularized,

the

codex.

The

oldest

codices

are

Bibles.

Indeed,

the

codex

was

such

an

improvement

that

it

caused

the

extinction

of

the

scroll

as

a

literary

vehicle

within

a

few

centuries.

Because

of

the

interest

early

Christians

had

in

expediting

Bible

reading

and

study,

it

is

hardly

an

exaggeration

to

say

that

they

were

responsible

for

giving

the

world the book.

What

is

more

important

is

how

the

codex

might

have

affected

how

the

Bible

was

viewed,

studied,

and

interpreted.

With

the

codex,

the

Bible’s

sixty-six

books

had,

for

the

first

time,

physically

become

one

Book,

so

that

John

Chrysostom,

in

the

fourth

century,

first

called

it

“the

Bible.”

Now,

Christians,

in

a

very

practical

sense,

could

see

the

Bible

as

one

book.

This

held

significant

implications.

It

raised

the

question

of

“canonicity,”

or

which

books

were

God’s

word

and,

therefore,

deserved

a

place

within

its

covers.

This,

in

turn,

led

to

an

appreciation

of

the

fact

that

a

book’s

contents

had

to

agree

with

the

other

books

in

the

Bible.

This

implied

that

the

Bible

was

to

be

treated

and

interpreted

holistically,

so

that

what

one

book

said

had

to

be

interpreted

in

the

light

of

what

every

other

book

in

the

Bible

said.

Because

the

Biblical

books

were

really

one

book,

this

meant

that

the

teaching

of

God’s

word

had

to

be

deduced

through

a

process

of

consulting

and

integrating

into

a

harmonious

whole

all

of

its

relevant

texts.

The

Bible

in

the

form

of

a

codex

made

it

practical

to

do

this.

It

allowed

a

Bible

student

to

do

in

seconds

what

took

the

scroll

user

minutes.

This

encouraged

the

comparison

and

integration

of

related

parts

of

the

Bible

and,

in

turn,

the

recognition,

confirmation, and presentation of Bible doctrine.

From

this

perspective,

then,

putting

the

books

of

the

Bible

together

in

a

codex

was

when

they

came

together as the Bible, and now as then, it must be treated and interpreted as one Book.

Copyright © 2017 - current year, Gary P. and Leslie G. Eubanks. All Rights Reserved.

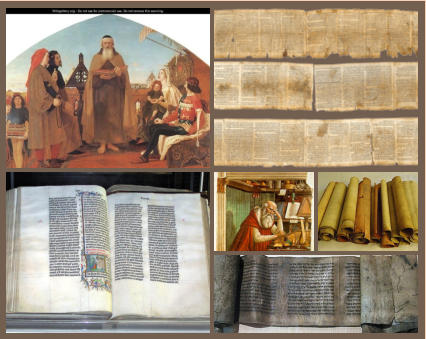

top,

left

to

right

-

"The

First

Translation

of

the

Bible

into

English:

Wycliffe

Reading

His

Translation

of

the

Bible

to

John

of

Gaunt";

“The

Great

Isaiah

Scroll”

-

housed

in

the Shrine of the Book in the Israel Museum

middle,

left

to

right

-

“

Saint

Jerome

in

His

Study,”

fresco

by

Domenico

Ghirlandaio

located

in

the

church

of

Ognissanti,

Florence;

100-600-year-old

scrolls

from

a

private collection

bottom, left to right - A Bible handwritten in Latin, on display in Malmesbury Abbey,

Wiltshire, England; “The Book of Esther,” from the 13th or 14th Century, on display

at the Musée du quai, Paris, France

---All attributions at page bottom---

• Ford Madox Brown – Creative Commons license, via Wikipedia Commons

• Ardon Bar Hama, author of original document is unknown, Public domain, via Wikimedia

Commons

• Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License 3.0, viWikipedia Commons

• Mike Izbicki, 2014-08-10- scribal traditions of "ancient" Hebrew scrolls, Creative

Commons attribution-share alike

• Adrian Pingstone. Public domain Wikimedia Commons

• Deror avi, 2009-02-13, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“And

I

saw

the

dead,

the

great

and

the

small,

standing

before

the

throne,

and

books

were

opened;

and

another

book

was

opened,

which

is

the

book

of

life;

and

the

dead

were

judged

from

the

things

which

were

written

in

the

books,

according

to

their

deeds”

(Revelation 20:12).

Codex: the Bible Becomes the Bible

The

use

of

“book”

in

the

Bible

is

an

anachronism,

since

books,

as

they

are

known

today,

did

not

then

exist.

Instead,

ancient

“books”

were

“scrolls,”

or

rolls

of

papyrus,

which

were

opened

by

being

unwound.

When

Jesus

“closed

the

book”

of

Isaiah

in

the

Nazareth

synagogue,

He

“rolled”

it

up

(Lk.

4:20).

John

said

the

sky

was

“split

apart

like

a

scroll

when

it

is

rolled

up”

(Rev.

6:14),

and

the

Psalmist

refers

to

“the

roll

of

the

book”

(cf.

Psa.

40:7;

Heb.

10:7,

NASB).

Thus,

to

translate

the

Greek

words,

“biblion”

or

“biblos”

(whence,

“Bible”),

as

“book”

is

an

accommodation to modern conceptions.

Moving

to

different

parts

of

a

scroll

was

cumbersome.

Bible

readers

are

now

accustomed

to

being

able

to

move

quickly

from

one

text

to

another,

but

this

was

not

easily

done

by

scroll

users.

In

fact,

the

larger

books

of

the

Bible

by

themselves

might

occupy

all

the

space

of

a

single

scroll.

For

example,

when

Jesus

was

given

the

scroll

of

Isaiah

(Lk.

4:17),

He

presumably

had

to

unroll

it

almost

to

its

end

to

find

the

place

from

which

He

read

(Isa.

61:1ff).

Adding

the

twenty-seven

New

Testament

books

increased

the

size

of

the

Bible

and

the

occasion

to

move

rapidly

among

Biblical

texts

for

cross-referencing.

So,

having

sixty-six

books

on

scrolls

became

inconvenient,

if

not

untenable,

for

the

kind

of

Bible

study which was needed.

This

situation

led

to

the

development

of

the

codex,

which

was

essentially

the

modern

book.

Codices

allowed

texts

to

be

written

on

the

fronts

and

backs

of

leaves,

or

pages,

which

were

piled

atop

one

another

in

textual

order

and

bound

together

by

stitching

on

one

edge

to

produce

a

book.

The

codex

had

the

great

advantage

of

giving

readers

access

to

a

large

amount

of

text

in

a

much

more

compact

and

usable

form,

and

especially

of

allowing

them

to

move

easily

from

one

text

to

another.

In

fact,

Christians

are

credited

with

having

developed,

or

popularized,

the

codex.

The

oldest

codices

are

Bibles.

Indeed,

the

codex

was

such

an

improvement

that

it

caused

the

extinction

of

the

scroll

as

a

literary

vehicle

within

a

few

centuries.

Because

of

the

interest

early

Christians

had

in

expediting

Bible

reading

and

study,

it

is

hardly

an

exaggeration

to

say that they were responsible for giving the world the book.

What

is

more

important

is

how

the

codex

might

have

affected

how

the

Bible

was

viewed,

studied,

and

interpreted.

With

the

codex,

the

Bible’s

sixty-six

books

had,

for

the

first

time,

physically

become

one

Book,

so

that

John

Chrysostom,

in

the

fourth

century,

first

called

it

“the

Bible.”

Now,

Christians,

in

a

very

practical

sense,

could

see

the

Bible

as

one

book.

This

held

significant

implications.

It

raised

the

question

of

“canonicity,”

or

which

books

were

God’s

word

and,

therefore,

deserved

a

place

within

its

covers.

This,

in

turn,

led

to

an

appreciation

of

the

fact

that

a

book’s

contents

had

to

agree

with

the

other

books

in

the

Bible.

This

implied

that

the

Bible

was

to

be

treated

and

interpreted

holistically,

so

that

what

one

book

said

had

to

be

interpreted

in

the

light

of

what

every

other

book

in

the

Bible

said.

Because

the

Biblical

books

were

really

one

book,

this

meant

that

the

teaching

of

God’s

word

had

to

be

deduced

through

a

process

of

consulting

and

integrating

into

a

harmonious

whole

all

of

its

relevant

texts.

The

Bible

in

the

form

of

a

codex

made

it

practical

to

do

this.

It

allowed

a

Bible

student

to

do

in

seconds

what

took

the

scroll

user

minutes.

This

encouraged

the

comparison

and

integration

of

related

parts

of

the

Bible

and,

in

turn,

the

recognition,

confirmation,

and

presentation

of

Bible

doctrine.

From

this

perspective,

then,

putting

the

books

of

the

Bible

together

in

a

codex

was

when

they

came

together

as

the

Bible,

and now as then, it must be treated and interpreted as one Book.